Developing Confident Horses

|

|

This page is a continuation from Part Two.

Horsenality: The combination of characteristics or qualities that form an individual horse's distinctive character. Horses each have distinctive personalities, or "horsenalities," if you will. How they respond to different training approaches will vary according to horsenality type. In training, one size definitely does not fit all. So it only makes sense to use an approach that will be the most successful with the particular horse that we are attempting to train. A number of trainers and clinicians have discussed this issue over the years, but the most thorough explanation to date has been presented by Parelli Natural Horsemanship. Rather than reconstruct this entire dialogue, here is a link to Horsenality Horse Training Dos and Doníts. Since these descriptions are the basis for this portion of this feature, we'll use the term "horsenality" in the context described by Parelli.

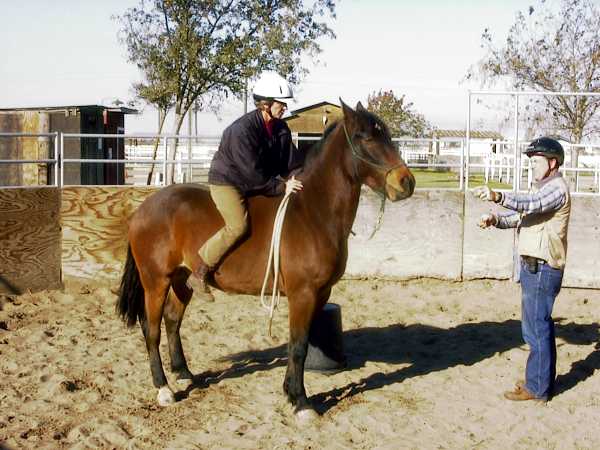

Confidence from the beginning. A wild horse's second time in halter and lead. |

Making the connection. The same wild horse's second time in halter and lead.

(With award-winning equestrian author Willy Klaeson who also helped gentle this horse.)

| From our experience, making a connection that produces trust and confidence begins with the horse recognizing that we are trying to understand him before we expect him to understand us. This is a primary difference between "mechanical" training and "communication-based" training. In the emergency services we have to base our actions on facts and probabilities. From our experience, training that focuses on effective two-way communication with the horse dramatically increases the probability of success, and we generally achieve that success in a much shorter period of time. |

Steady and reliable.

|

How the various "horsenalities" present themselves.

As stated earlier, we need to consider "horsonalities" as descriptions of horses' behavioral tendencies at a given point in time. These descriptions can be used as a basis for choosing handling and training approaches that encourage a given horse to respond more desirably and reliably. Modern neuroscience has shown that most horses are not stuck in such behavioral descriptions, and sometimes our preconceptions about a given horse can actually reinforce its undesirable behavior. Therefore the challenge is to determine the best approach in order to motivate the horse to respond favorably. To determine the best approach to use in training and developing a reliable horse, we first work on determining what "horsenality" combination we're working with. While horses can have traits that run the spectrum, we'll focus on the four trait combinations that typically present themselves. "Left-brained" Introverts. Left brained introverts are typically quietly curious ("nosy,") studying their surroundings. They are generally exceptionally good at reading human body language. They may appear stand-offish but will readily engage in training that they find interesting although they can become easily bored. They typically want to understand what's going on and can shut down or exhibit an unexpected stress response when the "input" exceeds their rate of processing. Oftentimes they do better when they are given a chance to stop and process during a difficult lesson rather than be pushed through it. They often don't exhibit their stress levels real-time and can surprise riders or handlers who aren't in tune with their horses by unexpectedly "blowing up" or completely shutting down. We've seen these horses actually lie down when pressured too hard. When approached, the left-brained introvert will usually exhibit, "I'm OK, you're OK. I'm just going to do my thing but ... if you have something that interests me I'll come over." |

A left-brained introvert will want to study unfamiliar situations. (This BLM horse was

deemed untrainable by two professional trainers who couldn't get him in halter and to lead.

He turned out to be one of the fastest learning horses we've handled. He just needed to "process"

what was going on. Third day we worked with him and and second day on the confidence obstacles.)

|

"Left-brained" Extroverts.

Left-brained extroverts are generally very curious, often "getting into things." They respond well to constructive training activities, are usually gregarious, and are pretty transparent in their emotions. They can also get easily bored but they typically exhibit their frustration more readily than introverts. Left-brained extroverts can be mischievous, learning how to open stall doors and gates, taking things apart and otherwise manipulating their environment including showing up in places where horses don't belong. A big challenge when training may well be keeping the horse interested and engaged so you don't discover that the horse has decided to do something completely different. When approached, the left-brained extrovert will often trot over to see what's going on and engage his handler. However left-brained extroverts can slip into a more introvertive state if the presentation of something unfamiliar or a new skill being taught is presented at a rate that exceeds their rate of comfortable processing. This slipping into an introvertive state is often misperceived as the horse being stubborn. |

Left-brained extroverts can be adventurous.

|

|

"Right-brained" Introverts.

Right-brained introverts are more defensive by nature and tend to be more shy and reclusive when in situations outside their comfort zones. These are horses where patience and finding a pace that is comfortable for the horse generally produces faster and more reliable results than pushing things. Being introverts they may not exhibit their stress levels real-time and can unexpectedly "act up" when they lose confidence. When approached, the right-brained introvert may appear watchful and shy, remaining calm or approaching only after the horse understands why the human is approaching.

Right-brained introverts often need patience and additional reassurance. |